Can You Trust 'Oldest and Best'?

- Issue Date: September/October 2017

When you see in your New King James Bible (NKJV) or even in some notes in the KJV that Mark 16:9-20 is not in the “oldest and best manuscripts, the Sinaiticus and Vaticanus,” do you ever ask: “Who says??” Obviously, those notes were not in the original written by Mark. So who put them there and are they right?

When you see in your New King James Bible (NKJV) or even in some notes in the KJV that Mark 16:9-20 is not in the “oldest and best manuscripts, the Sinaiticus and Vaticanus,” do you ever ask: “Who says??” Obviously, those notes were not in the original written by Mark. So who put them there and are they right?

Using modern research methods, linguist and author David W. Daniels has attempted to shed some light on that vital question. In an upcoming book on his research on the Sinaiticus, he relates a story that demonstrates the process of verifying the age of old manuscripts.

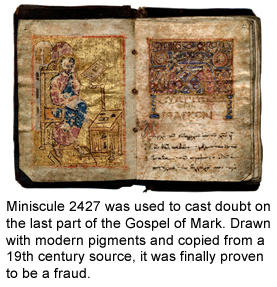

It seems that there is an old book of the Gospel of Mark that surfaced in the early 1900s. For want of a better name it is called Codex 2427 by paleographers (the scholars who claim expertise in dating old books and manuscripts.)

The history of 2427 was obscure but after “careful” examination, it was declared quite old and authentic —maybe more than 500 years— and put in the top category of Bible source manuscripts. It was presented as possibly closer to the original than anything else available. This reputation got it included as evidence in scholarly journals and text books.

Though wrinkled with age, it had little, painted illustrations. These piqued the interest of some other scientists who specialized in scientifically dating original art. They subjected the pigments of the ink to scientific analysis and discovered that the artist had used Prussian blue which was not invented until 1704. Further analysis discovered other pigments not known until the late 1800s.

Following his theory, he searched a number of libraries containing manuscripts of Mark. Finally he found a match in a translation of a copy of the Vaticanus by Philipp Buttmann in 1860. The line length matched the missing words from 2427. In addition, Buttmann had taken some liberty in his translation making some “personal choices” in his copy. These also showed up in 2427 confirming that Carlson had found the source document for 2427.

So, 2427 was not an early 14th century “Category 1” manuscript, but the product of some enterprising forger late in the 19th century. Yet, the best of the elite, modern “text scholars” had bought into the fake and included it in official journals and text books. Some publishers have, to date, neglected to remove the reference.

Daniels uses this story to illustrate the detective work necessary to validate “oldest and best” manuscripts.

Oddly enough, neither Vaticanus nor Sinaiticus have been subjected to these rigorous tests. In fact, Daniels discovered in his research that someone was poised to do exactly these kinds of tests on the Sinaiticus in April, 2015, but was mysteriously pulled off the project and reassigned to something else. There are no records of any further attempts, adding to Daniels’ conviction that text scholar Constantin Tischendorf’s claim that the Sinaiticus is “oldest” is highly suspect.

You can see why Daniels cautions Bible readers to take the notes in their Bibles with a grain of salt. They are not part of the preserved scripture, but the flawed opinions of uninspired men.

How glad that we have a whole, preserved Bible in the KJV, but we must be careful to put our faith in nothing but the Bible. When you distribute Chick tracts, you can be confident that you are delivering powerful scriptures from the Bible preserved by Christ’s promise in Matt. 24:35.

- See more articles on related topics:

- Bible Versions

- Codex Sinaiticus

- Sinaiticus

- History of Preservation

Other Articles from September/October 2017:

More on Bible Versions:

Products of Interest:

-

Is The "World's Oldest Bible" a Fake?

352 pages

Here is proof that the Sinaiticus, a supposedly ancient Bible text on which modern Bibles are based, is actually a 19th-century fake. -

Did Jesus Use the Septuagint?

112 pages

They're saying Jesus used the Septuagint. But what they really want is to add something to your Bible. -

Understandable History of the Bible

557 pages

You'll learn the history of the Bible in this well-documented but easy-to-understand book. -

Did the Catholic Church Give Us the Bible?

208 pages

The Bible has two histories. One is of God preserving His words through His people. The other is of the devil using Roman Catholic "scholars" to pervert God’s words and give us corrupt modern Bibles.